Tin Pan Alley

Tin Pan Alley

The term “Tin Pan Alley” refers to the physical location of the New York City-centered music publishers and songwriters who dominated the popular music of the United States in the late 19th century and early 20th century. Tin Pan Alley was the popular music publishing center of the world between 1885 to the 1920s.

Tin Pan Alley was West 28th Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenue in New York City. There is a plaque on the sidewalk on 28th St between Broadway and Fifth with a dedication. This block is now considered part of Manhattan’s Flatiron district.

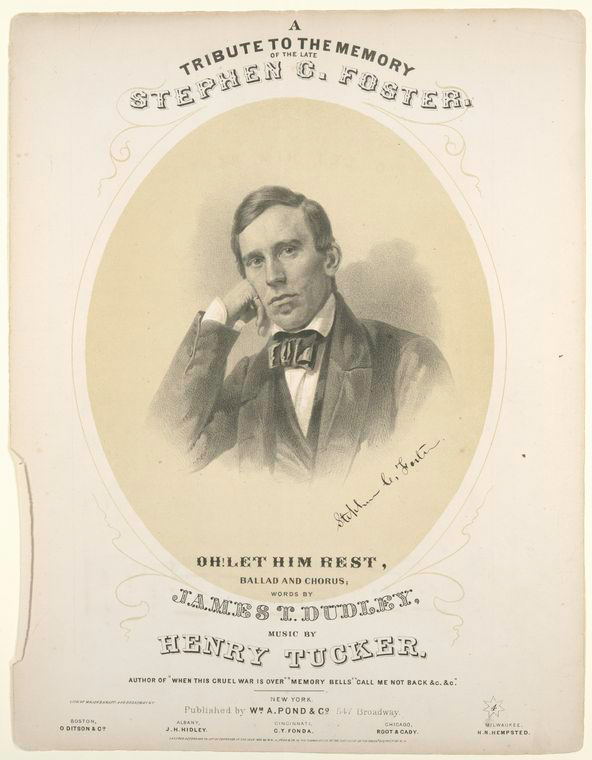

In the mid-1800s, copyright control on melodies was poorly regulated in the United States. Many competing publishers would often print their own versions of whatever songs were popular at the time. Stephen Foster’s songs, for example, probably generated millions of dollars in sheet music sales, but Foster saw little of it and died in poverty. With stronger copyright protection laws in the late 1800s, songwriters, composers, lyricists, and publishers started working together for mutual financial benefit.

Stephen Foster

Following the Civil War, more than 25,000 new pianos were sold each year and by 1887, over 500,000 youths were studying piano. The demand for sheet music indicated the size of the market for publishers. From 1885 through 1900 New York City began to emerge as the center of popular music publishing. New York had emerged as the center for the musical and performing arts. It was the incoming port for talent from overseas and the springboard for domestic talent headed overseas. It also had an established distribution network for the United States. In New York City, new trends were born, developed and exploited. During this period, the new generation of entrepreneurial music publishers grew and flourished.

Before 1885 there were important music publishers scattered throughout the country. Music publishing could be found in New York, Chicago, New Orleans, St. Louis, Philadelphia, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Detroit, Boston and Baltimore. Each publisher was involved in the printing and distribution of sheet music for church music, music instruction books, study pieces and classical items for home and school use and many were successful. Small local publishers (often connected with commercial printers or music stores) continued to flourish. When a tune became a significant local hit, rights to it were usually purchased from the local publisher by one of the bigger New York firms. Examples of some of the most successful were Thomas B. Harms (Harms, Inc. started in 1881) and Isadore Witmark (M. Witmark & Sons first published music in 1885). These concentrated on popular music. They were also pioneers in the use of market research to select music and then use aggressive marketing techniques to sell it.

Song composers were hired under contract giving the publisher exclusive rights to popular composers’ works. The market was then surveyed to determine what style of song was selling best. The composers were directed to compose more works in that style. Once written, a song was actually tested with both performers and listeners to determine which would be published and which would not. It was the music business — music had become an industry. Once published, song pluggers (performers who worked in music shops playing the latest releases) were hired to give the music exposure. Arrangements were made with popular performers of the day to use selected material for exposure (it was the birth of ‘Payola’). By the end of the century, a number of influential publishers had offices on 28th street between 5th Avenue and Broadway. This part of 28th street became known as “Tin Pan Alley.”

The name “Tin Pan Alley” is attributed to a newspaper writer named Monroe Rosenfeld. While he was staying in New York, he coined the term to articulate the cacophony of dozens of pianos being pounded at once in publisher’s demo rooms. He said it sounded like hundreds of people pounding on tin pans. During the years before air conditioning, New York City buildings had operable windows. The demonstration cubicles lined the front and alley walls of the buildings stretching for any natural daylight they could find. New York was hot in the summer and the windows would be wide open. The sounds would tumble to the street and bounce off the facing buildings. It must have sounded amazing. The term was used in a series of articles he wrote around 1900 – Like ‘Yankee Doodle Dandy’, the name eventually stuck and later came to describe the American music industry as a whole.

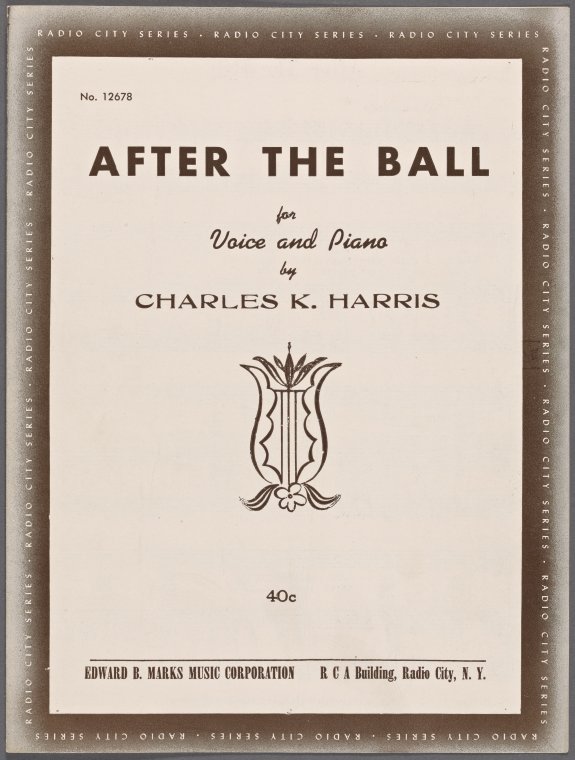

Vaudeville played an important role in the story of the American popular song. These shows were an effective showcase for new music. The publishing houses profited tremendously from the sale of songs made popular by these shows. The market potential for songs was enormous, even by today’s standards. Charles K. Harris’s ‘After The Ball’ (1892) sold over five million copies. Large numbers of songs from this period became widely known and remain popular in some circles today. Examples include ‘In the Good Old Summertime’ (1902), ‘Give My Regards To Broadway’ (1904), ‘Shine on Harvest Moon’ (1908), ‘Down by the Old Mill Stream’ (1910) and ‘Let Me Call You Sweetheart’ (1910).

Charles K. Harris – “After the Ball”

The music houses in lower Manhattan were lively places, with a steady stream of songwriters, vaudeville and Broadway performers, musicians, and song pluggers. Aspiring songwriters came to demonstrate tunes they hoped to sell. When tunes were purchased from unknowns with no previous hits, the name of someone with the firm was often added as co-composer (in order to keep a higher percentage of royalties within the firm), or all rights to the song were purchased outright for a flat fee (including rights to put someone else’s name on the sheet music as the composer). Songwriters who became established producers of commercially successful songs were hired to be on the staff of the music houses. The most successful of them, like Harry Von Tilzer and Irving Berlin, founded their own publishing firms.

Irving Berlin

Song pluggers were pianists and singers who made their living demonstrating songs to promote sales of sheet music. Most music stores had song pluggers on staff. Other pluggers were employed by the publishers to travel and familiarize the public with their new publications.

When vaudeville performers played New York City, they would often visit various Tin Pan Alley firms to find new songs for their acts. 2nd and 3rd, rate performers often paid for rights to use a new song, while famous stars were given free copies of publisher’s new numbers or were paid to perform them. This was valuable advertising.

Initially, Tin Pan Alley specialized in melodramatic ballads and comic novelty songs, but it embraced the newly popular styles of the cakewalk and ragtime music. Later, jazz and blues were incorporated, although less completely, as Tin Pan Alley’s primary orientation was producing songs that amateur singers or small-town bands could perform from printed music. Since improvisation, blue notes, and other characteristics of jazz and blues could not be easily captured in conventional printed notation, Tin Pan Alley manufactured jazzy and bluesy pop songs and dance numbers. Much of the public in the late 1910s and the 1920s did not know the difference between these commercial products and authentic jazz and blues.

Tin Pan Alley as the center of publishing activity began to dissipate around the start of the Great Depression in the 1930s when the phonograph and radio supplanted sheet music as the driving force of American popular music. Some consider Tin Pan Alley to have continued into the 1950s when earlier styles of American popular music were upstaged by the rise of rock’n’roll.

The rise of cinema and radio and the steady urbanization of the population contributed to the decline of Tin Pan Alley. As the airwaves brought the music directly into people’s homes, they had less need for printed sheet music. America’s use of free time was changing for good.

Music publishing, however, still had an important and profitable role in finding, creating, marketing and selling the American popular song. The business moved uptown with the new trends and changes in the business of music.

An article published by the Songwriters Hall of Fame best sums up the musical legacy of Tin Pan Alley, which extends to Rag Time, Blues, Jazz, Folk, Country and Broadway.

“Never in the history of American popular music were so many genres centered in one area… Between 1900 and 1910, more than 1800 “rags” had been published on Tin Pan Alley, beginning with “Maple Leaf Rag” by Scott Joplin. In 1912, [Tin Pan Alley composer] W.C. Handy introduced popular music to the underground sound of the Blues. By 1917, a recording by a new musician, Louis Armstrong, took over Tin Pan Alley and the 1920s were dedicated to the playing and recording of Jazz. Theatre, which had remained the entertainment of choice, fused all preceding stage shows–minstrel, vaudeville, musical comedy, revues, burlesque, and variety–to create the spectacular Broadway production. By 1926, the first movie with sound came creating a new outlet for production music. Folk and Country Music was introduced to mainstream audiences in the mid-1930s. Big bands and swing music defined the 1930s and 40s, introducing new accompanying vocalists such as Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday. In the early 40s, publishers imported Latin American sound from Brazil, Mexico and Cuba and English lyrics were adapted to foreign themes…”

In 1985, a trailblazing, prolific pop songwriter named Bob Dylan stated, “Tin Pan Alley is gone. I put an end to it. People can record their own songs now.”

Below is a list of the most impactful and top-selling Tin Pan Alley songs, courtesy of Dave Whitaker at Dave’sMusicDatabase.com.

Daniel Decatur Emmett “Dixie” (1860)

Henry J. Sayers “Ta-Ra-Ra Boom-De-Ay” (1891)

Charles K. Harris After the Ball (1892)

Theodore August Metz and Joe Hayden “A Hot Time in the Old Town” (1896)

Charles B. Lawlor and James W. Blake “The Sidewalks of New York” (1894)

Paul Dresser “On the Banks of the Wabash” (1897)

Joseph E. Howard and Ida Emerson “Hello Ma Baby” (1899)

Scott Joplin “Maple Leaf Rag” (1899)

Harry Von Tilzer and Arthur J. Lamb “A Bird in a Gilded Cage” (1900)

Hughie Cannon and Johnnie Queen “Bill Bailey, Won’t You Please Come Home” (1902)

Ren Shields and George Evans “In the Good Old Summertime” (1902)

Scott Joplin “The Entertainer” (1902)

Gus Edwards and Vincent Bryan “In My Merry Oldsmobile” (1902)

Richard H. Gerard and Harry Armstrong “Sweet Adeline (You’re the Flower of My Heart)” (1903)

George M. Cohan “Give My Regards to Broadway” (1904)

Arthur B Sterling and Kerry Mills “Meet Me in St. Louis, Louis” (1904)

Harry Von Tilzer and Andrew B. Sterling “Wait Till the Sun Shines, Nellie” (1905)

George M. Cohan “Yankee Doodle Boy” (1905)

George M. Cohan “You’re a Grand Old Flag (aka “The Grand Old Rag”)” (1906)

Gus Edwards and Will D. Cobb “School Days (When We Were a Couple of Kids)” (1907)

Jack Norworth and Albert von Tilzer “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” (1908)

Jack Norworth and Nora Bayes “Shine on, Harvest Moon” (1908)

Edward Madden and Gus Edwards “By the Light of the Silvery Moon” (1909)

Joseph E. Howard, Harold Orlob, Frank R. Adams, and Will M. Hough “I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now” (1909)

Fred Fisher and Alfred Bryan “Come Josephine in My Flying Machine” (1910)

Shelton Brooks “Some of These Days” (1910)

Leo Friedman and Beth Slater Whitson “Let Me Call You Sweetheart” (1910)

Tell Taylor “Down by the Old Mill Stream” (1910)

Harry Von Tilzer and William Dillon “I Want a Girl Just Like the Girl Who Married Dear Old Dad” (1911)

Irving Berlin “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” (1911)

Nat D. Ayer and Seymour Brown “Oh You Beautiful Doll” (1911)

W.C. Handy, George A. Norton, Charles Tobias, and Peter DeRose “The Memphis Blues” (1912)

Edward Madden and Percy Wenrich “Moonlight Bay” (1912)

Chris Smith and Jim (James Henry) Burris “Ballin’ the Jack” (1913)

Alfred Bryan and Fred Fisher “Peg O’ My Heart” (1913)

Jimmy Monaco and Joseph McCarthy “You Made Me Love You (I Didn’t Want to Do It)” (1913)

W.C. Handy “St. Louis Blues” (1914)

Alfred Bryan and Al Piantadosi “I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier” (1915)

Euday L. Bowman “Twelfth Street Rag” (1916)

George M. Cohan “Over There” (1917)

George Meyer, Edgar Leslie, and E. Ray Goetz “For Me and My Gal” (1917)

Shelton Brooks “Darktown Strutters’ Ball” (1917)

Turner Layton and Henry Creamer “After You’ve Gone” (1918)

Sam M. Lewis, Joe Young, and Jean Schwartz “Rock-a-Bye Your Baby with a Dixie Melody” (1918)

The Original Dixieland Jazz Band, Harry DeCosta “Tiger Rag” (1918)

Jean Kenbrovin and John William Kellette “I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles” (1919)

John Schonberger, Richard Coburn, and Vincent Rose “Whispering” (1920)

George Gershwin and Irving Caesar “Swanee” (1920)

Buddy DeSylva and Louis Silvers “April Showers” (1922)

Turner Layton and Henry Creamer “Way Down Yonder in New Orleans” (1922)

Gus Kahn, Ernie Erdman, and Dan Russo “Toot Toot Tootsie (Goo-Bye!)” (1922)

Gus Kahn and Walter Donaldson “Carolina in the Morning” (1923)

Frank Silver and Irving Cohn “Yes! We Have No Bananas” (1923)

Spencer Williams and Jack Palmer “Everybody Loves My Baby” (1924)

Isham Jones and Gus Kahn “It Had to Be You” (1924)

Walter Donaldson and Gus Kahn “Yes Sir! That’s My Baby” (1925)

Isham Jones and Gus Kahn “I’ll See You in My Dreams” (1925)

Vincent Youmans and Irving Caesar “Tea for Two” (1925)

Ben Bernie, Kenneth Casey, and Maceo Pinkard “Sweet Georgia Brown” (1925)

Irving Berlin “Always” (1926)

Ray Henderson, Sam Lewis, and Joe Young “Five Foot Two, Eyes of Blue” (1926)

Ray Henderson and Mort Dixon “Bye Bye Blackbird” (1926)

Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II “Ol’ Man River” (1927)

Harry M. Woods “Side by Side” (1927)

Irving Berlin “Blue Skies” (1927)

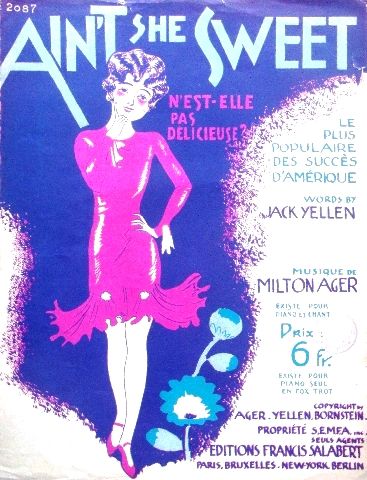

Milton Ager and Jack Yellen “Ain’t She Sweet?” (1927)

Walter Donaldson and George A. Whiting “My Blue Heaven” (1927)

Hoagy Carmichael and Mitchell Parish “Stardust” (1927)

Jimmy McHugh and Dorothy Fields “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love” (1928)

Walter Donaldson and Gus Kahn “Makin’ Whoopee” (1928)

Mark Fisher, Joe Goodwin, and Larry Shay “When You’re Smiling, the Whole World Smiles with You” (1928)

Victor Young and Will Harris “Sweet Sue, Just You” (1928)

Joe Burke and Al Dubin “Tip Toe Through the Tulips” (1929)

Johnny Green, Eddie Heyman, Robert Sour, and Frank Eyton “Body and Soul” (1930)

Irving Berlin “Puttin’ on the Ritz” (1930)

Hoagy Carmichael and Stuart Gorrell “Georgia on My Mind” (1930)

Jimmy McHugh and Dorothy Fields “On the Sunny Side of the Street” (1930)

Milton Ager and Jack Yellen “Happy Days Are Here Again” (1930)

George and Ira Gershwin “I Got Rhythm” (1930)

Herman Hupfield “As Time Goes By” (1931)

Hoagy Carmichael and Sidney Arodin “Lazy River” (1931)

Seymour Simons and Gerald Marks “All of Me” (1931)

Harry Akst, Sam M. Lewis, and Joe Young “Dinah” (1932)

Cole Porter “Night and Day” (1932)

Harold Arlen and Ted Koehler “Stormy Weather (Keeps Rainin’ All the Time)” (1933)

Jerome Kern and Otto Harbach “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” (1933)

Cole Porter “I Get a Kick Out of You” (1934)

Irving Berlin “Cheek to Cheek” (1935)

Cole Porter “Begin the Beguine” (1935)

George & Ira Gershwin “Summertime” (1935)

Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart “Blue Moon” (1935)

Cole Porter “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” (1936)

Arthur Johnson and Johnny Burke “Pennies from Heaven” (1936)

George & Ira Gershwin “They Can’t Take That Away from Me” (1937)

Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart “My Funny Valentine” (1937)

Irving Berlin “God Bless America” (1939)

Harold Arlen and E.Y. “Yip” Harburg “Over the Rainbow” (1939)

Johnny S. Black “Paper Doll” (1942)

Irving Berlin “White Christmas” (1942)

The Brill Building

Scores of music publishers had offices in the Brill Building. During the ASCAP strike of 1941, many of the composers, authors and publishers turned to pseudonyms in order to have their songs played on the air. Brill Building songs were constantly at the top of the Hit Parade and played by the leading bands of the day including:

- The Benny Goodman Orchestra

- The Glenn Miller Orchestra

- The Jimmy Dorsey Orchestra

- The Tommy Dorsey Orchestra

Publishers included:

- Leo Feist Inc.

- Lewis Music Publishing

- Mills Music Publishing

Composers included:

- Billy Rose

- Buddy Feyne

- Johnny Mercer

- Irving Mills

- Peter Tinturin

Racial Politics of Music Publishing

The music publishers at this time followed the racial codes of the day. They either had their own (typically white) contract writers composing songs or they opened their doors to publish songs of others, but hid the fact that songs were created by non-white or non-Christian artists. Jewish songwriters often adopted anglicized noms de plume in order for their songs to be published. This was necessary at a time when antisemitism was widespread.

In the 1930s some publishers in the Brill Building specialized in publishing the songs of African American Swing composers. For example, Lewis Music published the songs of Erskine Hawkins and Avery Parrish, among others. These tunes were called “Race Music”, the euphemism for songs written by black artists. If a composer wrote an instrumental (and even sometimes if there were already lyrics), the publishers provided their own lyricists. Top selling songs on the (white) Hit Parade, such as Tuxedo Junction and Jersey Bounce, were originally composed as instrumentals by black swing artists, but were not played by white bands on the radio until they had been published with lyrics, often by white writers.

The Brill Building was regarded as one of the most prestigious addresses in New York for music business professionals. By 1962 the Brill Building contained 165 music businesses — a musician could find a publisher and printer, cut a demo, promote the record, and cut a deal with radio promoters, all within this one building. The creative culture of the independent music companies of Brill Building and the nearby 1650 Broadway came to define the style of popular music.

Carole King described the atmosphere at the ‘Brill Building’ publishing houses of the period. “Every day we squeezed into our respective cubby holes with just enough room for a piano, a bench, and maybe a chair for the lyricist if you were lucky. You’d sit there and write and you could hear someone in the next cubbyhole composing a song exactly like yours. The pressure in the Brill Building was really terrific — because Donny (Kirshner) would play one songwriter against another. He’d say, ‘We need a new smash hit’ — and we’d all go back and write a song and the next day we’d each audition for Bobby Vee’s producer” (quoted in The Sociology of Rock by Simon Frith (1978, ISBN 0-09-460220-4).

Writers

Many of the best works in this diverse category were written by a loosely affiliated group of songwriter-producer teams — mostly duos — that enjoyed immense success and who collectively wrote some of the biggest hits of the period. Many in this group were close friends, as well as being creative and business associates — and both individually and as a duo, they often worked with each other and with other writers in a wide variety of combinations.

- Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller

- Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman

- Gerry Goffin and Carole King

- Ellie Greenwich and Jeff Barry

- Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil

- Burt Bacharach and Hal David

- Neil Sedaka and Howard Greenfield

- Hugo & Luigi

- Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart

Other famous musicians who were headquartered in The Brill Building:

- Laura Nyro

- Claus Ogerman

- Neil Diamond

Among the hundreds of hits written by this group are Leiber and Stoller’s “Yakety Yak,” Shuman and Pomus’ “Save The Last Dance For Me,” Bacharach and David’s “The Look of Love,” Sedaka and Greenfield’s “Calendar Girl,” King and Goffin’s “The Loco-Motion,” Mann and Weil’s “We Gotta Get Out of This Place” and Spector, Greenwich and Barry’s “River Deep Mountain High.”

Aldon Music – 1650 Broadway

Many of these writers came to prominence while under contract to Aldon Music, a publishing company founded ca. 1958 by aspiring music entrepreneur Don Kirshner and industry veteran Al Nevins. Aldon was not initially located in the Brill Building, but rather, a block away at 1650 Broadway (at 51st St.). In fact, 1650 was built to be a musician’s headquarters, so much so that the laws at the time required that the “front” door be placed on the side of the building due to laws restricting musicians from entering buildings from the front. Most so-called ‘Brill Building’ writers began their careers at 1650, and the building continued to house many record labels throughout the decades.

Portions Edited and expanded from Wikipedia

Special thanks to Rick Reublin of the website Parlor Songs for historical insight.

If you would like to use content from this page, see our Terms of Usage policy.

© 2008 Leonard Wyeth