Vaudeville

1871 – Vaudeville

‘Vaudeville’ comes from the French “vaux de ville”: ‘worth of the city’ or worthy of the city’s patronage. Like everything else in Vaudeville, however, the name was probably selected for sounding quaintly foreign and exotic. No one needed to know what it really meant – it was intended to mean Entertainment! The term ‘Vaudeville’ first appeared around 1871 with “Sargent’s Great Vaudeville Company” of Louisville, Kentucky.

Variety shows, for public entertainment, had been around forever in one form or another. The public tastes for entertainment shifted by region and influence. The Wild West Shows, for example, brought the mythology of the untamed West to Eastern urban audiences. Circuses brought exotic animals from all corners of the earth to insulated American communities. There were dime-museums, amusement parks, riverboats and town halls for family-friendly entertainment. There were traveling Medicine shows for comedy, music, acrobats, jugglers and novelties with their strange potions, tonics, salves, and miracle elixirs. For more adult-oriented entertainment there were music halls, saloons, burlesque and whore houses. Minstrel shows offered a variety of entertainment in the 1840s. These are particularly noteworthy as being uniquely American. Vaudeville embodied bits and pieces of all of these itinerant amusements. It was fundamentally American: as wild and varied as the ‘melting pot’ of the great American experiment itself.

Burlesque Dancers

The 1840s, ’50s and ’60s brought an explosion of cultural upheaval: the gold rush, the Western expansion, the Civil War, the industrial revolution, mechanization, the railways, the discovery of how to make steel, Darwin’s Origin of the Species and so on. The culture and the economy were being fueled by waves of immigration, Italian, Irish (following the potato famine), Chinese, Jewish, etc. This was the land of opportunity. Urban areas began to swell with the steady flow of fresh arrivals feeding insatiable factories. People began to make money. Not just the rich, but ordinary workers began to have enough money to buy houses and furnishings. They seemed to want stuff and this created markets for more goods. More goods meant more factories and more jobs. The cycle created a middle class. These folks had some free time and spare cash. Leisure time means entertainment.

Around 1880 a former circus ringmaster turned theater manager named Tony Pastor saw the potential and spending power of the new middle class and offered “polite” variety programs in several of his New York City theaters. His shows were relatively clean and family oriented and he didn’t allow the sale of liquor in his theaters. The experiment worked. It wasn’t long before other theater owners and promoters followed suit.

In 1887 The Bijou Theater was opened in Boston, Massachusetts by Benjamin Franklin Keith and Edward F. Albee. B.F. Keith began his show business career in the 1870s working as a grifter and barker with traveling circuses and for dime museums in New York City. In 1883 he moved to Boston and opened a museum of his own featuring Baby Alice the Midget Wonder and other acts. This generated enough income to allow B.F. Keith to build The Bijou Theatre. It was lavish and “fireproof.” Keith established a “fixed policy of cleanliness and order.” There was to be no vulgar or coarse material in any of his acts. The entertainment was to appeal to women and children. He promised, “a Sunday School dignitary to judge propriety at rehearsals.” This became the model for Vaudeville theater productions.

Keith reinforced a theater image of gentility by including famous acts from the “legitimate” stage. Not to be too ‘high brow,’ he also maintained light comedy from previous variety acts. There was something for everybody. Boston’s powerful Catholic Church took notice and supported the expansion of Keith’s enterprise on the promise of more clean entertainment. Keith and Albee went on to build more elaborate theaters in Boston and then expanded to other Northeastern cities.

Following any financially successful enterprise, there are always imitators. They appeared quickly all over the country and included managers like Marcus Loew (of Loew’s Theaters). By the 1890s theatre circuits could be found in every major city and many minor locations. There were comprehensive networks of booking offices that handled all the promotion and production. Keith and Albee consolidated their control of Vaudeville through United Booking Artists and through the establishment of the Vaudeville Manager’s Association. Keith and Albee held a monopoly that lasted well past Keith’s death in 1914.

Wherever people gather, new ideas are exchanged. News travels and ideas are disseminated. It wasn’t only theatricals, culture, politics and humor but also music. The musical presentations on the Vaudeville stages brought new musical styles to urban areas all over the country. Successful acts traveled the Vaudeville circuits, hitting all the major cities. It was a massively effective way to expose large portions of the population to new musical trends. If it was popular in New York, it would find its way across the country to audiences everywhere. The banjo, mandolin and guitar all played roles on the Vaudeville stage but the banjo was best suited to the task. It was small, loud and dependable.

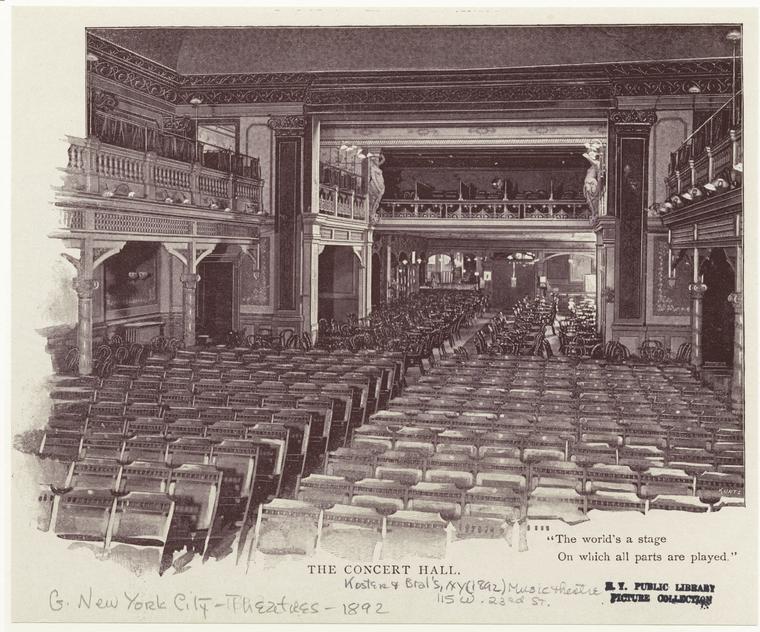

The introduction of moving pictures began to change the face of vaudeville. They were low-priced and could run all day long. The first public showing of movies projected on a screen took place at Koster and Bial’s Music Hall in 1896. Lured by greater salaries and easier working conditions, many early film and old-time radio performers, such as W. C. Fields, Buster Keaton, the Marx Brothers, Edgar Bergen, and Jack Benny, used the prominence they gained in live performances to vault into movies. (By doing this, they often exhausted in a few moments of screen time the novelty of an act that might have kept them on tour for years.) Other vaudevillians who helped vaudeville’s decline include The Three Stooges, Abbott and Costello, Kate Smith, Bob Hope, Judy Garland, and Rose Marie, who used vaudeville as a launch pad for movie careers.

Koster & Bial

During the teens, moving pictures steadily grew in popularity. By the late 1920s, almost all vaudeville bills included moving pictures. Earlier in the century, many vaudevillians, understanding the threat represented by movies, held out hope that the silent nature of the “flickering shadow sweethearts” would protect their place in the public’s affection. With the introduction of talking pictures in 1926, the film studios removed the last argument in favor of live theatrical performance — spoken dialogue.

New York City’s Palace Theatre, vaudeville’s epicenter, changed exclusively to the cinema on November 16th, 1932. This could be viewed as the end for vaudeville. In fairness, it was still alive and withered gradually.

Theater owners discovered that rental costs of films vs. the price of performers, newly unionized stagehands, booking fees, lighting, orchestra, etc. vastly increased their profits. Performers tried hanging on for a time in combination shows (often referred to as “vaudefilm”) in which live performances accompanied a film presentation. Inevitably, managers further trimmed costs by eliminating costly live performances. Vaudeville also suffered in the rise of broadcast radio following the greater availability of inexpensive receiver sets later in the 1920s.

The 1930s saw the standardization of film distribution. By 1930, the vast majority of live theatres had been wired for sound and none of the major studios were producing silent pictures. For a time, the most luxurious theatres continued to offer live entertainment, but the majority of theatres were forced by the Great Depression to economize.

Though talk of its resurrection was heard throughout the 1930s and after, the demise of the supporting apparatus of the circuits and the higher cost of live performance made any large-scale renewal of vaudeville unrealistic. The times had changed an art form forever.

If you would like to use content from this page, see our Terms of Usage policy.

ⓒ 2008, Leonard Wyeth