Musicals - Theater, Movie and Video

Back to Research > History > Musical Styles and Venues in America

Musicals, both theatrical, movie and video, have been a popular form of American entertainment for more than a century. Some people love it and others claim to hate it, but all agree that the emotional and entertainment content is high. Musicals have consistently been profitable forms of public entertainment demonstrating that Americans will financially support the arts that they like.

Musical theater, for the purposes of this article, does not include opera. Opera is generally built around a musical work requiring the primary talents of operatic singer(s). Furthermore, opera may or may not be performed in the language of the audience and depends more on the music than the story. The storyline of an opera supports the musical vocal and orchestral masterwork.

The purpose of discussing musical theater has to do with its impact on popular music and musical tastes. For this article, musicals are defined by popular entertainment that combines a story with music, songs (lyrics), spoken dialog and dance. The emotional content of the piece – its humor, drama, pathos, love, anger – as well as the story itself, is communicated through the words, music, dance and theater as an integrated whole. We’ll call them simply: “musicals”.

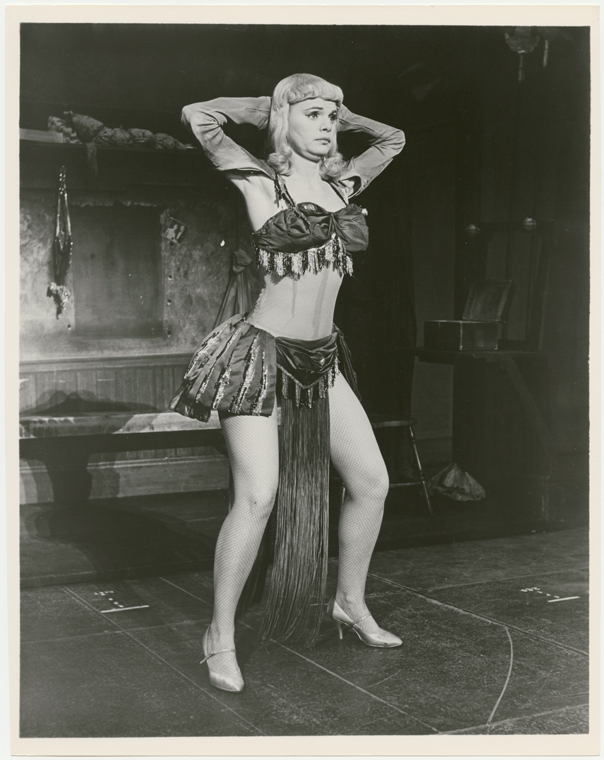

In concept, musicals attempt to tap into and seamlessly integrate emotion and fantasy into a storyline. The musical’s moments of drama can reach their greatest intensity when performed in song and dance. When the emotion becomes too strong for speech, you sing. When the emotion becomes too strong for song, you dance. The songs are crafted to suit the characters and their roles inside the story. As New York Times critic Ben Brantley described the ideal of song in musical theater (reviewing the 2008 revival of Gypsy): “There is no separation at all between song and character, which is what happens in those uncommon moments when musicals reach upward to achieve their ideal reasons to be.”

Musical – Gypsy

Structure and Purpose

The three primary components of a musical are the music, the lyrics and the book. ‘The book’ of a musical is the story. In opera this would be the libretto (Italian for “little book”). The music and lyrics together form the score of the musical. The creative team, including a director, a musical director and a choreographer, determines how the musical is presented. The 20th-century “book musical” might be defined as a musical play where the songs and dances are fully integrated into a well-made story, with serious dramatic goals, that is able to evoke genuine emotions (including laughter). The storylines suitable for musicals generally follow a pattern: An individual (outsider) finds a person, situation or community that they want to be part of. They struggle to be understood. There are usually several situational misunderstandings followed by an epiphany, understanding and resolution. The resolution usually involves a chorus and crescendo – fulfillment of the original dream. There are, of course, many exceptions – including historical drama. The common thread appears to be the expression of love and understanding.

Musicals say something important about fantasy and community: Everyone wants to fit in. We all want to be members of a tribe of like-minded friends – a community of mutual understanding. One person singing to another (or to no one at all) is able to articulate what they are feeling with dramatic force. But, as story lines begin to resolve, the players reach some form of mutual understanding. This is usually expressed by the chorus – the full community. The voices and ideas become so unified that they can be expressed in harmony – the full community in agreement, singing and dancing as one, in perfect harmony. It’s fantasy – no resemblance to real life – but effectively strikes a familiar chord in most hearts. We all wish we could be that well understood, be that close to our communities, and live in that degree of harmony. Now, that’s entertainment!

The melodies and moods need to be simple, memorable and appropriate to the story. When the music and lyrics perfectly support the message, they become irresistibly memorable. They become tied to the message – tied to the story. The emotion of the full story becomes ingrained in the meaning of the song. Imagine the ability to imbue friendship, empathy, heartache and hope into a single song.

Musical theater uses the oldest tricks in the book to manipulate the human heart:

It begins with repetition: the musical opens with an overture, introducing and familiarizing the ear to the melodies and harmonies that will follow. The clues to the harmonic arrangements are freely revealed early making them easy to identify later.

Some version of the musical’s predominant melody is used early on in the story to help reveal the character of the protagonist(s). Minor and secondary melodies are used to help develop the supporting characters and help build tension and emotion.

Bits and pieces of the predominant melody are interspersed to keep it fresh in the mind of the audience.

As the story develops toward a resolution, the harmonic complexity of the predominant melody builds and expands.

The resolution includes a full chorus and a fully developed predominant melody. As the audience wanders out into the real world humming the predominant melody, it literally has become part of their consciousness: the melody and lyrics have taken on the full depth and breadth of the play. That is the type of music that stays with the audience forever. Like Pavlov’s dog, each time they hear the melody, they experience some portion of the emotional content of the play.

Brief History

Ancient Greece and The Middle Ages

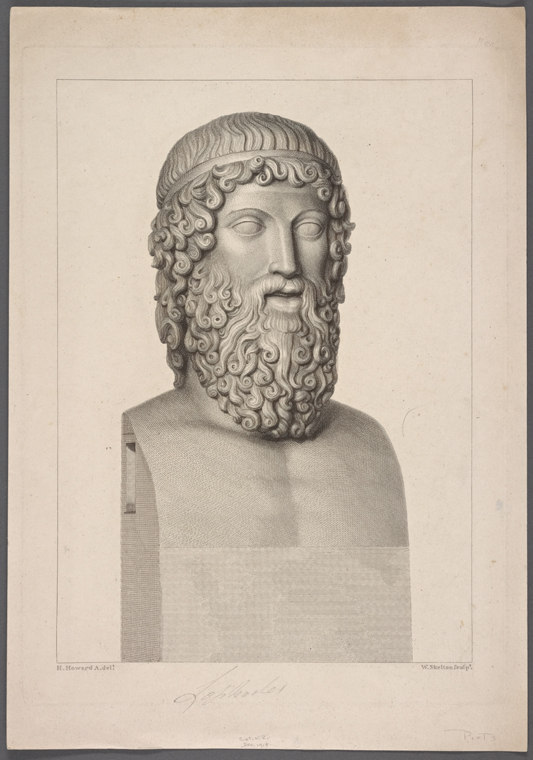

Musical theater in Europe dates back to the ancient Greeks, who included music and dance in their stage comedies and tragedies in the 5th century BCE. Aeschylus and Sophocles composed their own music to accompany their plays and choreographed the dances of the chorus. The 3rd-century BCE Roman comedies of Plautus included song and dance routines performed with orchestrations. The Romans introduced technical innovations: including making the dance steps more audible in large open-air theaters. Roman actors attached metal chips called “sabilla” to their stage footwear – the first tap shoes.

Sophocles

By the Middle Ages, theater in Europe consisted mainly of traveling minstrels and small performing troupes of performers singing and offering slapstick comedy. In the 12th and 13th centuries, religious dramas, such as The Play of Herod and The Play of Daniel taught the liturgy, set to church chants. Later “Mystery plays” were created that told a biblical story in a sequence of entertaining parts. Several pageant wagons (stages on wheels) would move about the city, and a group of actors would tell their part of the story. Once finished, the group would move on with their wagon, and the next group would arrive to tell its part of the story. These plays developed into an autonomous form of musical theater, with poetic forms sometimes alternating with the prose dialogues and liturgical chants. The poetry was provided with modified or completely new melodies.

Renaissance to the 1700s

The Renaissance developed these forms into Commedia Dell’Arte, an Italian tradition where raucous clowns improvised their way through familiar stories, and from there, opera buffa. Molière turned several of his farcical comedies into musical entertainments with songs (music provided by Jean Baptiste Lully) and dance in the late 1600s. Arts of all kinds became widely popular, including musical theater.

Scene from Don Juan by Molière

By the 1700s, two forms of musical theater were popular in Britain, France and Germany: ballad operas, like John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera (1728), that included lyrics written to the tunes of popular songs of the day (often spoofing opera), and comic operas, with original scores and mostly romantic plot lines, like Michael Balfe’s ‘The Bohemian Girl’ (1845). Other musical theater forms developed by the 19th century, such as Vaudeville, British Music Hall, Melodrama and Burlesque. Melodramas and Burlettas, in particular, were popular in part because most London theaters were licensed only as music halls and not allowed to present plays without music. In any event, what a piece was called did not necessarily define what it was. The Broadway extravaganza ‘The Magic Deer’ (1852) advertised itself as “A Serio Comico Tragico Operatical Historical Extravaganzical Burletical Tale of Enchantment.”

Current Musical Play Examples:

- Wicked

- Man of La Mancha

- Hello, Dolly!

- Camelot

- The Sound of Music

- West Side Story

- My Fair Lady

- Beauty and the Beast

- Chicago

- Mamma Mia!

- Grease

- Evita

- Phantom of the Opera

- South Pacific

- The King and I

Musical Videos:

- MTV

- VH-1

- YouTube

- MySpace

- various websites

Movie Musicals

Musical plays are easily translated to film. Film offers the ability for special effects, rapid scene changes and flashbacks, carefully controlled natural landscapes and expansive choruses with studio orchestral arrangements. The genre allows greater possibilities of emotional manipulation – including levels of intimacy that the distance between stage actors and the audience could never allow. As a consequence, many of the most successful stage musicals are translated to film. Occasionally the opposite is also true: good film non-musical stories are translated to stage musicals (like ‘The Lion King’).

Television Musicals

“Made for TV” movie musicals were popular in the 1990s (for example ‘Gypsy’ (1993), and ‘Cinderella’ (1997)). Several made-for-TV musical movies in the 2000s were actually adaptations of the stage version, such as ‘South Pacific’ (2001), ‘The Music Man’ (2003) and ‘Once Upon A Mattress’ (2005), and a televised version of the stage musical ‘Legally Blonde’ (2007). Several musicals were filmed on stage and broadcast on Public Television, for example, ‘Contact’ (2002) and ‘Kiss Me Kate’ and ‘Oklahoma!’ (2003).

Some recent television shows have set their episodes as musicals. Examples include episodes of ‘Ally McBeal,’ ‘Buffy the Vampire Slayer’ (episode Once More, with Feeling), ‘That’s So Raven’, Daria’s episode ‘Daria!’, ‘Oz’s Variety,’ ‘Scrubs’ (one episode was written by the creators of Avenue Q), and the 100th episode of ‘That ’70s Show’. Others have included scenes where characters suddenly begin singing and dancing in a musical-theater style during an episode, such as in several episodes of ‘The Simpsons’, ‘30 Rock’, ‘Hannah Montana’, ‘South Park’ and ‘Family Guy’.

“American Idol” and similar programs have spotlighted both talented and un-talented aspiring youth across America and delivered as entertainment. The audience appears to be equally entertained by the ridicule of those who believe they are talented and fall short, as well as the fearless and innocent raw talent of kids from all walks of American life. In either event, the central concept is that kids who can really deliver a traditional pop song in a dramatic (strictly formula) way, are to be idolized.

“Glee” has revived the television musical by cleverly introducing a wide variety of musical styles reinterpreted by immensely talented actors and delivered on a weekly basis. The soap opera-style plots are as thin as they can be, since the core of the program is the music and talent. Regardless, the formula appears to work as the show is currently a hit.

Music Videos

Music Television (MTV) and VH-1 extended the musical concept to musical videos. The promotion of a popular band’s music becomes easier if there is a story or set of compelling imagery to help imbue meaning into the music. This also helped shape the image of the bands. The notion worked for a number of years until the intensity of market saturation and the disconnect between the striking imagery and the music appears to have lost appeal to the general public.

Post Script

According to the Broadway League (formerly The League of American Theaters and Producers), for the 2007–08 season, 12.27 million tickets were sold for Broadway shows with a gross sale amount of almost a billion dollars. During the 2006-07 season, approximately 65% of Broadway tickets were purchased by tourists (16% of which were foreign). This does not include off-Broadway and small venues. The Society of London Theater reported that 2007 total attendees in the major commercial and grant-aided theaters in Central London were 13.6 million, with total ticket revenues of £469.7 million – setting a new record.

Stephen Sondheim, however, has the following view:

“You have two kinds of shows on Broadway – revivals and the same kind of musicals over and over again, all spectacles. You get your tickets for The Lion King a year in advance, and essentially a family… pass on to their children the idea that that’s what the theater is – a spectacular musical you see once a year, a stage version of a movie. It has nothing to do with theater at all. It has to do with seeing what is familiar… I don’t think the theater will die per se, but it’s never going to be what it was… It’s a tourist attraction.”

For whatever reason, the numbers suggest that he is wrong.

If you would like to use content from this page, see our Terms of Usage policy.© 2008, Leonard Wyeth

Expanded and edited from numerous sources including Wikipedia