John and Alan Lomax

Edited and expanded from research from Wikipedia and other sources by Leonard Wyeth

With the help and support of the Library of Congress; many (or most) of the collected recordings and images (including videos) of John and Alan Lomax are now available online.

John Lomax records Richard Amerson at a home in Alabama (Photo: Library of Congress)

The Lomax Family Cultural Equity Project

John Avery Lomax 1867-1948

John Avery Lomax (September 23rd, 1867 – January 26th, 1948) was a pioneering musicologist and folklorist. Lomax was born in Goodman, Mississippi and grew up in central Texas. He was raised on a farm and lived the life of a Texas farmer for the first 28 years of his life. He was surrounded by the music of the rural Texan countryside. He became fascinated it the ability of the simple ballads to give voice to the stories of their lives.

In 1895, at age 28, Lomax entered the University of Texas at Austin to study English literature. He brought with him a roll of cowboy songs he had written down in childhood. He showed them to an English professor, only to have them discounted as simple, cheap and unworthy, prompting him to take the bundle behind the men’s dormitory and burn it. Lomax focused his attention on more mainstream academic pursuits. After graduation, he worked as the University of Texas as registrar, manager of Brackenridge Hall (the men’s dormitory on campus), and personal secretary to the President of the University. In 1903 he accepted an offer to teach English at Texas A&M University and settled down with his new wife, Bess Brown Lomax.

His early interest in cowboy songs never really left him. He felt the depth of artistic expression but couldn’t find anyone interested in documenting it. English Literature was culture, cowboy songs were sentimental trivia.

In 1907 Lomax learned of two scholars at Harvard University, Barrett Wendell and George Lyman Kittredge, who actively encouraged research into folklore. He moved to become a graduate student at Harvard for the chance to work with the scholars. Both Wendell and Kittredge continued to play an important advisory role in his career long after he returned to Texas the following year, Master of Arts degree in hand, to resume his teaching position at A&M. Encouraged by Wendell, he applied for, and was awarded, a Sheldon grant to research and collect cowboy songs. The resulting anthology, Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads, published in 1910, with an introduction by President Theodore Roosevelt, made him famous. Included were “The Buffalo Skinners,” which George Lyman Kittredge called “one of the greatest western ballads” and which was praised for its Homeric quality by Carl Sandburg and Virgil Thompson. From the first, John Lomax insisted on the racial inclusiveness of American folklore. Some of the most famous songs in the book — “Get Along Little Doggies,” “Sam Bass,” and “Home on the Range” was credited to black cowboys.

1909 – Texas Folklore Society

Around the same time, Lomax and Professor Leonidas Payne of the University of Texas at Austin co-founded the Texas Folklore Society, following Kittredge’s suggestion that Lomax establish a Texas branch of the American Folklore Society. Lomax and Payne hoped that the society would further their own research while kindling an interest in folklore among like-minded Texans. On Thanksgiving Day, 1909, Lomax nominated Payne as president of the society, and Payne nominated Lomax as secretary. The two set out to marshal support, and a month later, Killis Campbell, an associate professor at the university, publicly proposed the formation of the society at a meeting of the Texas State Teachers Association in Dallas. By April 1910, there were ninety-two charter members (one of whom was Lomax’s former student, John B. Jones). In the inaugural issue of the Publications of the Texas Folklore Society, John A. Lomax urged the collection of Texas folklore: “Two rich and practically unworked fields in Texas are found in the large Negro and Mexican populations of the state.” He adds, “Here are many problems of research that lie close at hand, not buried in musty tomes and incomplete records, but in vital human personalities.” These were oral traditions that changed with every new generation. Songs could be written down as one method of recording the works – and the music could be transcribed – but the flavor of the music was lost as the bards that sang them died off. The invention of the recording machine, however, created a way to capture the oral tradition for all time.

The society grew gradually over the next decade, with Lomax steering it forward. At his invitation, Kittredge and Wendell attended its meetings. Other early members were Stith Thompson and J. Frank Dobie, who both began teaching English at the university in 1914. At Lomax’s recommendation, Thompson became the society’s secretary/treasurer in 1915. In 1916, Thompson edited the first volume of the Publications of the Texas Folklore Society, which Dobie reissued as Round the Levee in 1935. This publication exemplified the society’s express purpose, and the motivation behind Lomax’s own work: to gather a body of folklore before it disappeared, and to preserve it for the analysis of later scholars. These early efforts foreshadowed what would become Lomax’s greatest achievement, the collection of more than ten thousand recordings for the Archive of American Folk Song at the Library of Congress.

In June 1910, Lomax accepted an administrative job at the University of Texas. Throughout the next seven years, he continued his research, and also undertook lecture tours, assisted and encouraged by his wife and children. All this came to an end in 1917, however, when Lomax was fired along with six other faculty members as the result of a political battle between Governor James Ferguson and the university president, Dr. R. E. Vinson. Lomax moved to Chicago to accept a job as a banker. Shortly afterward, Ferguson was impeached and the Board of Regents rescinded its dismissal of the faculty, but Lomax did not return to his former job. Instead, he divided the next fifteen years between banking (first in Chicago and later in Dallas) and working with various University of Texas alumni groups. He also continued to lecture at major universities and sometimes taught individual folk song classes for his former professors at Harvard, thus maintaining his valuable network of contacts. He also became close friends with poet Carl Sandburg, who frequently mentions him in his book, American Songbag (1927).

Archive of American Folk Song

In 1931, Bess Brown Lomax died at the age of 50, leaving four children (the youngest, Bess, only ten years old). In addition, the Dallas bank where Lomax worked failed: he had to phone his customers one by one to announce that their investments were worthless. In debt and unemployed at the height of the Great Depression and with two school-age children, the 65-year-old slipped into his own depression. In hope of reviving his father’s spirits, John Lomax Jr. encouraged him to begin a series of lecture tours. With no other options, they took to the road, camping to save money, with John Jr. (and later Alan Lomax) serving the senior Lomax as driver and personal assistant. In June 1932, they arrived at the offices of the Macmillan publishing company in New York. Here Lomax proposed his idea for an anthology of American ballads and folksongs, with a special emphasis on the contributions of African Americans. It was accepted. In preparation, he traveled to Washington to review the holdings in the Archive of American Folk Song of the Library of Congress.

By the time of Lomax’s arrival, the Archive already contained a collection of commercial phonograph recordings that straddled the boundaries between commercial and folk, and wax cylinder field recordings, built up under the leadership of Robert Winslow Gordon, Head of the Archive, and Carl Engel, chief of the Music Division. Gordon had also experimented in the field with a portable disc recorder, but did not have the time nor resources to do much significant fieldwork. Lomax found the recorded holdings of the Archive woefully inadequate for his purposes. He made an arrangement with the Library to provide recording equipment (by grants), in exchange for which he would travel the country making field recordings for deposit into the Archive. John Lomax was paid a salary of one dollar per year for this work (which included fundraising for the Library) and was expected to support himself entirely through writing books and giving lectures.

Thus began a ten-year relationship with the Library of Congress that would involve not only John but the entire Lomax family, including his second wife, Ruby Terrill Lomax, whom he married in 1934. All four of John’s children assisted with his folksong research and with the daily operations of the Archive — Shirley, who performed songs taught to her by her mother; John Jr., who encouraged his father’s association with the Library; Alan Lomax who accompanied John on field trips and in 1937 and became the Archive’s first paid nominally employee as Assistant in Charge; and Bess, who spent her weekends and school vacations copying song text and doing comparative song research.

The Field recordings

Through a grant from the American Council of Learned Societies, Lomax was able to set out in June 1933 on the first recording expedition under the Library’s auspices, with 18-year-old Alan Lomax in tow. They recorded songs sung by sharecroppers and prisoners in Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi.

Then, as now, a disproportionate percentage of African American males were held as prisoners. Robert Winslow Gordon, Lomax’s predecessor at the Library of Congress, had written (in an article in the New York Times, c. 1926) that, “Nearly every type of song is to be found in our prisons and penitentiaries” Folklorists Howard Odum and Guy Johnson also had observed that, “If one wishes to obtain anything like an accurate picture of the workaday Negro he will surely find his best setting in the chain gang, prison, or in the situation of the ever-fleeing fugitive.” John and Alan were able to put these ideas into practice. In their successful grant application they wrote, that prisoners, “Thrown on their own resources for entertainment . . . still sing, especially the long-term prisoners who have been confined for years and who have not yet been influenced by jazz and the radio, the distinctive old-time Negro melodies.” They toured Texas prison farms recording work songs, reels, ballads, and blues from prisoners such as James “Iron Head” Baker, Mose “Clear Rock” Platt, and Lightnin’ Washington. By no means were all of those whom the Lomaxes recorded imprisoned, however — in other communities, they recorded K.C. Gallaway and Henry Truvillion.

In July of 1933 they acquired a state-of-the-art, 315-pound acetate phonograph disk recorder. Installing it in the trunk of his Ford sedan, Lomax soon used it to record, at the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola, a twelve-string guitar player by the name of Huddie Ledbetter, better known as “Lead Belly,” whom they considered one of their most significant finds. During the next year and a half, father and son continued to make disc recordings of musicians throughout the South.

It may seem ironic that Lomax used the most up-to-date technology in order to preserve traditional art forms that he saw as endangered by the new, commercial recording industry and by radio. Unlike, virtually all previous amateur collectors, however, Lomax was no mere antiquarian. For his books emphasized that folk music creation is a dynamic, artistic process that is still happening today. By making this music better known and appreciated by a broad public, he hoped to encourage its continuance. In contrast to earlier amateur collectors the Lomaxes were also among the first to attempt to apply a scholarly methodology in their work.

John A. Lomax has also been accused of paternalism and of tailoring Lead Belly’s repertoire and clothing. “But,” writes jazz historian Ted Gioia, “few would deny the instrumental role he played in the transformation of the one-time convict into a commercially successful performer of traditional African American music. The turnabout in his life was rapid and profound — Lead Belly was released from prison on August 1st, 1934; his schedule for the last week of December that year included performances for the MLA gathering in Philadelphia, for an afternoon tea in Bryn Mawr, and for an informal gathering of professors from Columbia and NYU. Even by the standards of the entertainment industry,… this was a remarkable transformation.” Three months later Lomax and Lead Belly had a parting of the ways, never to be reunited, but Lead Belly went on to a fifteen-year career as an independent artist.

After the departure of Robert Gordon from the Library in 1934, Lomax was named Honorary Consultant and Curator of the Archive of Song (salary: one dollar a year), and he secured grants from the Carnegie Corporation and the Rockefeller Foundation, among others, for continued field recordings. He and Alan recorded Spanish ballads and vaquero songs on the Rio Grande border and spent weeks among French-speaking Acadians in southern Louisiana.

The Legacy

Lomax’s contribution to the documentation of American folk traditions extended beyond the Library of Congress Music Division through his involvement with two agencies of the Works Progress Administration. In 1936, he was assigned to serve as an advisor on folklore collecting for both the Historical Records Survey and the Federal Writers’ Project. As the Federal Writers’ Project’s first folklore editor, Lomax directed the gathering of ex-slave narratives and devised a questionnaire for project fieldworkers to use. This work was continued by Benjamin A. Botkin, who succeeded Lomax as the Project’s folklore editor in 1938, and at the Library in 1939 resulting in the invaluable compendium of authentic slave narratives, Lay My Burden Down: A Folk History of Slavery, edited by B. A. Botkin (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1945)

John A. Lomax’s autobiography Adventures of a Ballad Hunter (New York, Macmillan) was published in 1947 and immediately optioned to be made into a movie starring Bing Crosby in the title role, with Josh White as Lead Belly, but unfortunately it was never made. He died of a stroke in January 1948, age 79. On June 15th of that year, Lead Belly gave a concert at the University of Texas, performing children’s songs such as “Skip to my Lou” and spirituals (performed with his wife Martha) that he had first sung years before for the late collector.

Following in his grandfather’s footsteps, Lomax’s grandson John Lomax III is a nationally published US music journalist, author of Nashville: Music City USA (1986), Red Desert Sky (2001) and co-author of The Country Music Book (1988). He is also an artist manager and has represented Townes Van Zandt, Steve Earle, Rocky Hill, David Schnaufer and The Cactus Brothers. He began representing the Dead Ringer Band in 1996.

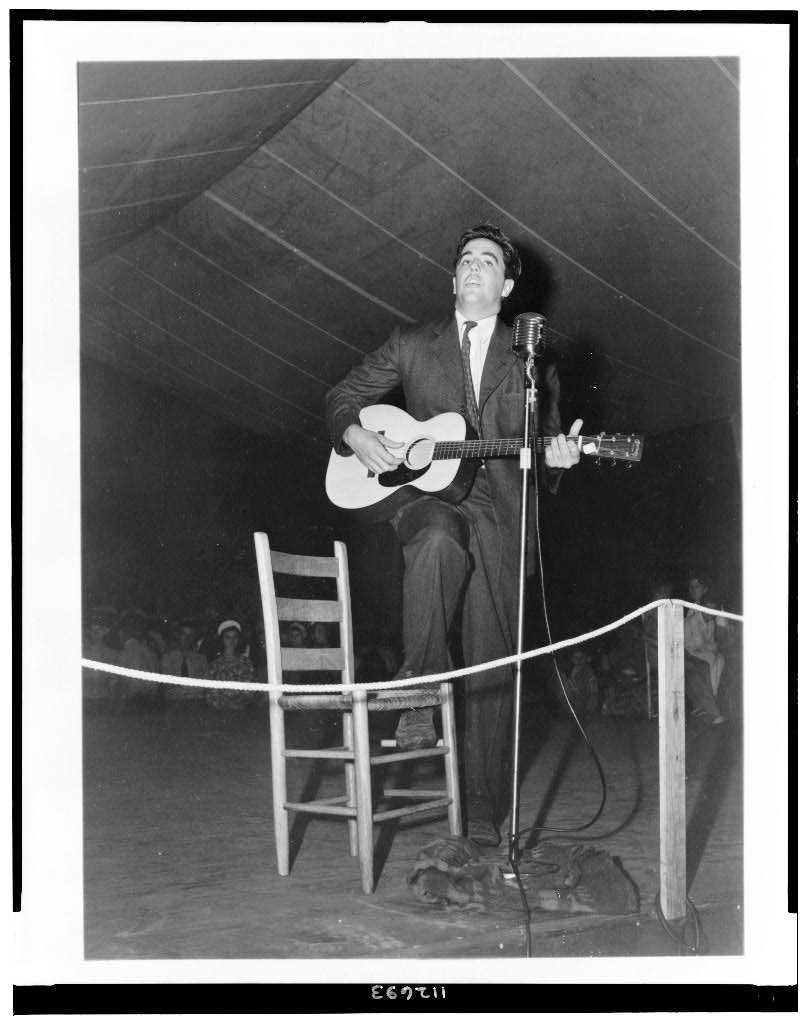

Alan Lomax circa 1945 (Courtesy of Lomax Archives)

Alan Lomax 1915-2002

Alan Lomax (January 15th, 1915 – July 19th, 2002), son of John A. Lomax, carried on in the tradition of his father as an American folklorist and musicologist. He attended The Choate School in Wallingford, Connecticut and went on to earn a degree in philosophy from the University of Texas at Austin. He continued his graduate studies with Melville J. Herskovits at Columbia and with Ray Birdwhistell at the University of Pennsylvania. To some, he is best known for his theories of Cantometrics, Choreometrics and Parlametrics, elaborated from 1960 until his death with the help of collaborators Victor Grauer, Conrad Arensberg, Forrestine Paulay, and Roswell Rudd.

From 1936 to 1942 Lomax was “Assistant in Charge” of the Archive of Folk Song of the Library of Congress to which he, his father and numerous collaborators contributed more than 10,000 field recordings. During his lifetime, he collected folk music from the United States, Haiti, the Caribbean, Ireland, Great Britain, Spain, and Italy, assembling treasure trove of American and international culture.

1940s

A pioneering oral historian, he also recorded interviews with many legendary folk musicians, including Woody Guthrie, Lead Belly, Muddy Waters, Jelly Roll Morton, Irish singer Margaret Barry, Scots ballad singer Jeannie Robertson, and Harry Cox of Norfolk, England, among many others. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor he took his recording machine into the streets to capture the reactions of everyday citizens. While serving in the army in World War II he made numerous radio programs in connection with the war effort. He also produced recordings, concerts, and radio shows, in the U.S and England, which played an important role in both the American folk music revival and British folk revivals of the 1940s and 50s.

In the late 1940s, he produced a series of folk music albums for Decca records and organized a series of concerts at New York’s Town Hall and Carnegie Hall, featuring blues, Calypso, and Flamenco music. He also hosted a radio show, Your Ballad Man, from 1945-49 that was broadcast nationwide on the Mutual Radio Network and featured a highly eclectic program, from gamelan music, to Django Reinhardt, to Klezmer music, to Sidney Bechet and Wild Bill Davidson, to jazzy pop songs by Maxine Waters and Jo Stafford, to readings of the poetry of Carl Sandburg, to hillbilly music with electric guitars, to Finnish brass bands — to name a few (See Matthew Barton and Andrew L. Kaye, in Ronald D. Cohen (ed), Alan Lomax Selected Writings, p. 98-99).

1950s

Lomax spent the 1950s based in London, from where he edited the 18-volume Columbia World Library of Folk and Primitive Music, an anthology issued on newly invented LP records. For the British and Irish volumes, he worked with the BBC and folklorists Peter Douglas Kennedy, Scots poet Hamish Henderson, and with Séamus Ennis in Ireland, where they recorded Irish traditional musicians, including some of the songs in English and Irish of Elizabeth Cronin in 1951. He also hosted a folk music show on BBC’s home service and organized a “skiffle” group, Alan Lomax and the Ramblers (who included Ewan Macoll, Peggy Seeger, and Shirley Collins, among others). His ballad opera Big Rock Candy Mountain premiered December 1955 at Joan Littlewood’s Theater Workshop and featured Ramblin’ Jack Elliot.

Lomax and Diego Carpitella’s survey of Italian folk music for the Columbia World Library, conducted in 1953 and 1954, with the cooperation of the BBC and the Accademia di Santa Cecilia in Rome, helped capture a snapshot of a multitude of important traditional folk styles shortly before they disappeared. The pair amassed one of the most representative folk song collections of any culture. From Lomax’s Spanish and Italian recordings emerged one of the first theories explaining the types of folk singing that predominate in particular areas, a theory that incorporates work style, the environment, and the degrees of social and sexual freedom.

Upon his return to New York in 1959, Lomax produced a concert, “Folksong ’59,” in Carnegie Hall, featuring Arkansas singer Jimmy Driftwood; the Selah Jubilee Singers and Drexel Singers (gospel groups); Muddy Waters and Memphis Slim (blues); the Stony Mountain Boys (bluegrass); Pete and Mike Seeger (urban folk revival); and The Cadillacs (a rock and roll group). The occasion marked the first time rock and roll and bluegrass were performed on the Carnegie Hall Stage. “The time has come for Americans not to be ashamed of what we go for, musically, from primitive ballads to rock ‘n’ roll songs,” Lomax told the audience. According to Izzy Young, the audience booed when he told them to lay down their prejudices and listen to rock ‘n’ roll. In Young’s opinion, “Lomax put on what is probably the turning point in American folk music . . . . At that concert, the point he was trying to make was that Negro and white music were mixing, and rock and roll was that thing” (quoted in Ronald D. Cohen’s Rainbow Quest, University of Massachusetts Press, 2002, p. 140).

Alan Lomax was married for 12 years to Elizabeth Harold Lomax, who assisted him in recording in Haiti, Alabama, Appalachia, and Mississippi, and who wrote radio scripts of folk operas featuring American music, broadcast over the BBC as part of the war effort, as well as conducting lengthy interviews with folk music personalities. He also did important field work with Elizabeth Barnicle and Zora Neale Hurston in Florida and the Bahamas; with John Work and Lewis Jones in Mississippi; with folksingers Robin Roberts and Jean Ritchie in Ireland; with his second wife Antoinette Marchand in the Caribbean; with Joan Halifax in Morocco; and with his daughter, Anna L. Chairetakis. All those who assisted and worked with him were accurately credited on the resultant Library of Congress, and other recordings, as well as in his many books and publications.

Alan Lomax met twenty-year-old English folk singer Shirley Collins while living in London. The two were romantically involved and lived together for some years. When Lomax obtained a contract from Atlantic Records to re-record some the U.S. artists he had recorded in the 1940s, using improved recording equipment, Collins accompanied him. Their folk song-collecting trip to the Southern states lasted from July to November 1959 and resulted in many hours of recordings, featuring performers such as Almeda Riddle, Hobart Smith, and Bessie Jones and culminated in the discovery of Mississippi Fred McDowell. Recordings from this trip were issued under the title Sounds of the South and some were also featured in the Coen brothers’ film Oh Brother, Where Art Thou. Lomax wanted to marry her but when their trip was over, Collins returned to England and instead married Austin John Marshall. In an interview in The Guardian newspaper, Friday March 21 2008, Collins was miffed that Alan Lomax’s 1993 history of blues music, The Land Where The Blues Began, barely mentioned her. “All it said was, ‘Shirley Collins was along for the trip’. It made me hopping mad. I wasn’t just ‘along for the trip’. I was part of the recording process, I made notes, I drafted contracts, I was involved in every part”. Collins decided to rectify the perceived omission in her memoir America Over the Water, published in 2004.

1960s and Beyond

In 1962, Lomax and singer and Civil Rights Activist Guy Carawan, music director at the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee, produced the album, Freedom in the Air: Albany Georgia, 1961-62, on Vanguard Records for the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee.

Lomax was a consultant to Carl Sagan for the Voyager Golden Record sent into space on the 1977 Voyager Spacecraft to represent the music of the earth. Music he helped choose included the blues, jazz, and rock ‘n’ roll of Blind Willie Johnson, Louis Armstrong, and Chuck Berry; Andean panpipes and Navajo chants; a Sicilian sulfur miner’s lament; polyphonic vocal music from the Mbuti Pygmies of Zaire, and the Georgians of the Caucasus; and a shepherdess song from Bulgaria by Valya Balkanska; in addition to Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven, and more.

The 1944 “ballad opera” The Martins and the Coys broadcast in Britain (but not the USA) by the BBC, featuring Burl Ives, Woody Guthrie, Will Geer, Sonny Terry, Pete Seeger, and Fiddlin’ Arthur Smith, among others, was released on Rounder Records in 2000.

Lomax’s 1993 Atlantic recording, Sounds of the South: A Musical Journey From the Georgia Sea Islands to the Mississippi Delta, features several songs sampled in Moby’s album Play, including “Natural Blues” (“Trouble So Hard”).

Alan Lomax received the National Medal of Arts from President Reagan in 1986, a Library of Congress Living Legend Award in 2000, and was awarded an Honorary Doctorate in Philosophy from Tulane University in 2001. He won the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Ralph J. Gleason Music Book Award in 1993 for his book ‘The Land Where the Blues Began’, connecting the story of the origins of Blues music with the prevalence of forced labor in the pre-World War II South (especially on the Mississippi levees). Lomax also received a posthumous Grammy Trustees Award for his lifetime achievements in 2003.’Jelly Roll Morton: The Complete Library of Congress Recordings’ by Alan Lomax (Rounder Records, 8-CD boxed set) won in two categories at the 48th annual Grammy Awards ceremony held on Feb 8th, 2006.

John and Alan Lomax are largely responsible for keeping many of the rural oral traditions of folk music alive. The depth of their research and field recordings is almost immeasurable. It is fair to say, however, that the shape of American music from the 1960s forward is due in some part to the work of the Lomax family.

If you would like to use content from this page, see our Terms of Usage policy.

© 2008, Leonard Wyeth