Carnegie Hall

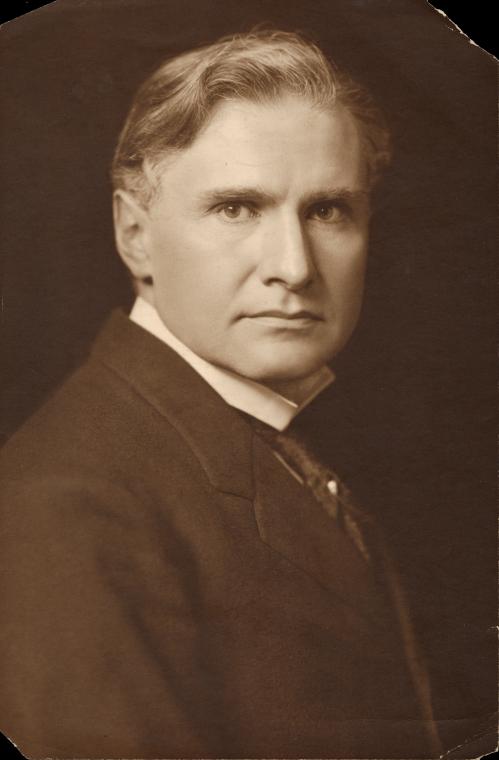

The story of Carnegie Hall begins in the spring of 1887. A 25-year-old Walter Damrosch (1862–1950) had attained the elevated position of conductor and musical director of the Symphony Society of New York and the Oratorio Society of New York. He had just finished his second season and took a sabbatical to Europe for a summer of study with conductor Hans von Bülow. Before air conditioning, New York summers were too hot for orchestral performances. It is not difficult to imagine the feel of ground-floor theaters packed with people, burning gas lamps and no air circulation in the years before deodorant.

Walter Damrosch

Damrosch inherited a vision for a grand concert hall for New York City from his father Leopold, who had founded the Oratorio Society in 1873 and the Symphony Society in 1878. The Symphony Society had a difficult time booking concerts into any of the available halls large enough to accommodate them. The Metropolitan Opera House was the best venue but it was controlled by the schedule of the resident opera company and the Philharmonic Society, considered New York’s primary orchestra at the time. The Oratorio Society was compelled to give its concerts in the showrooms of piano companies: Chickering, Steinway and Knabe, located on 14th Street.

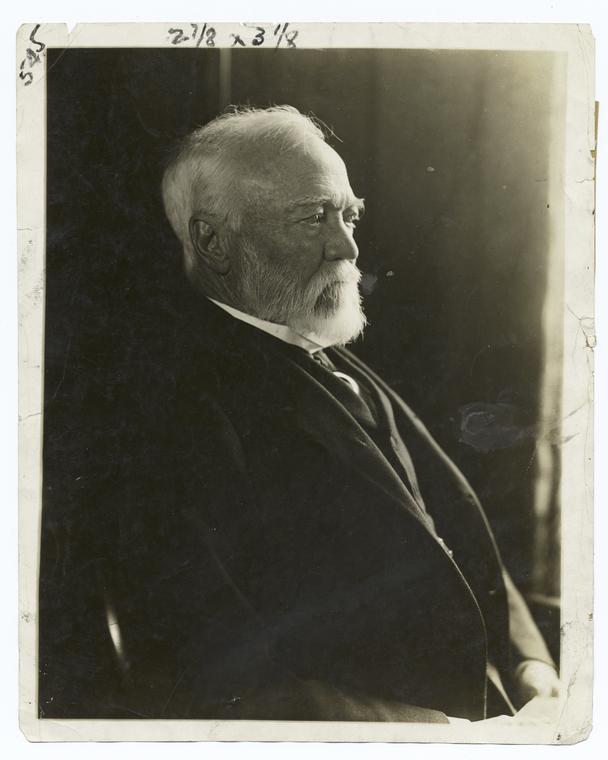

In the spring of 1887, traveling by sail from New York to London aboard The Fulda, maestro Damrosch chanced to meet the celebrated Scottish-born American steel magnate Andrew Carnegie. Carnegie (1835 to 1919), then 52, was taking his bride, 30-year-old Louise Whitfield on a honeymoon to Scotland. Louise Whitfield was the daughter of a well-to-do New York merchant and had sung in the soprano section of the Oratorio Society for several seasons. Carnegie took a liking to Damrosch and the three arranged a meeting at the end of the summer at the estate Kilgraston in Scotland. It was there that the idea of Carnegie Hall was born.

Andrew Carnegie

Carnegie agreed to help build a grand hall to be the finest concert venue in New York. In 1889, he formed a stock company, The Music Hall Company of New York, Ltd., and acquired seven parcels of land along the block of Seventh Avenue between 56th and 57th Streets, which were not yet paved. The location, at the edge of Goat Hill was a short distance from Central Park and so far uptown that it was considered suburban. Carnegie assumed a seat on the board of both the Symphony Society of New York and the Oratorio Society of New York.

The Design and Construction of The Music Hall

William Burnet Tuthill, an architect who had served on the board of the Oratorio Society and had a fondness for music as a cello player, was appointed chief architect. Architects Adler and Sullivan and Richard Morris Hunt were retained as consultants. Isaac A. Hopper and Company assumed the responsibility of general contractor. On May 13th, 1890 Mrs. Carnegie cemented the cornerstone with a silver trowel from Tiffany’s. She kept this memento on her mantelpiece for the rest of her life. Carnegie’s contribution eventually reached $2 million; approximately 90 percent of the total cost.

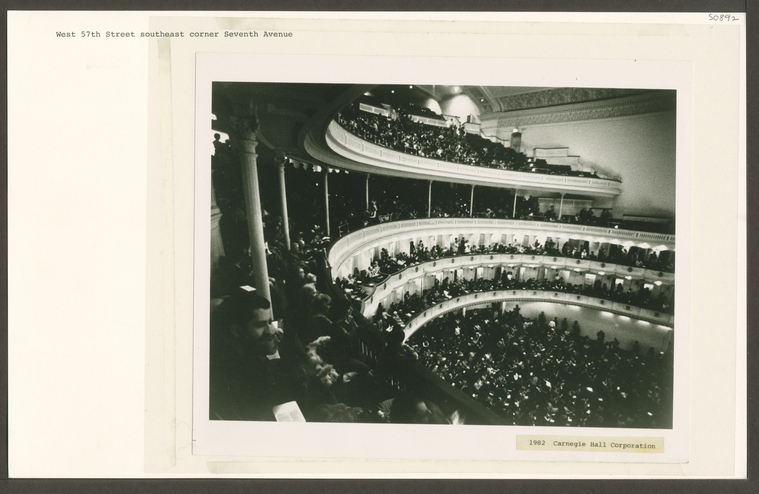

The plans called for a rectangular six-story structure housing three performance spaces:

- The Main Hall, seating 2,800

- A recital hall (located below the Main Hall) seating 1,200

- A chamber music hall (adjacent to the Main Hall), seating 250

- Above the chamber music hall were assembly rooms “suitable for lectures, readings, and receptions as well as chapter and lodge rooms for secret organizations.”

Carnegie Hall

Carnegie Hall is one of the last large structures in New York City built entirely of masonry. The building was designed not to require steel support beams using the Guastavino process, with concrete and masonry walls several feet thick. This turned out to be a good choice, considering the acoustical properties of the chosen materials. The heavy masonry effectively acoustically isolated the halls while providing good reflective and diffractive surfaces to enhance musical performances. Several flights of additional studio spaces were added to the building around 1900. For these, a steel framework was erected around segments of the building. Studios above the Hall contained working spaces for artists in the performing and graphic arts including music, drama, dance, as well as architects, playwrights, literary agents, photographers, and painters.

The building was completed in the spring of 1891. The five-day opening festival attracted the cream of New York society: Whitneys, Sloans, Rockefellers, and Fricks – who paid $1 to $2 for performances by the Symphony Society and the Oratorio Society under the direction of maestro Walter Damrosch and Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. Opening night, May 5th, 1891, Horse-drawn carriages lined the streets for a quarter mile outside the Hall. The Music Hall was filled to capacity. After a dedication speech from Bishop Henry Codman Potter, Damrosch led the Symphony Society in a performance of Beethoven’s Leonore Overture No. 3.

Tchaikovsky stepped up to the podium to conduct his Marche Solennelle. The concert closed with the Berlioz Te Deum. Beyond the talent onstage and the glamour in the audience, the reviews of that inaugural night focused on the Hall. “Tonight, the most beautiful Music Hall in the world was consecrated to the loveliest of the arts. Possession of such a hall is in itself an incentive for culture.” proclaimed one newspaper and another: “It stood the test well!” The reviews were unanimous — the “Music Hall founded by Andrew Carnegie” was an overwhelming success.

The term “Music Hall” to many European artists, suggested a vaudeville palace rather than a serious concert hall. Initially, Andrew Carnegie had no interest in having his name formally attached to the civic structure. After a period of negotiations and appeals to Carnegie to use his name, he relented. During the 1894–95 season, the name of the Music Hall was officially changed to “Carnegie Hall.”

The prestige of a Carnegie Hall appearance has attracted most of the world’s finest performers to its stages. Carnegie Hall has become the essential venue in the United States and a litmus test of greatness. The public appreciated from the earliest performances that these halls served as a showcase of American culture. As such, they were not limited to classical music, opera and dance but to all forms of public performance. In the days before radio and television, Carnegie Hall allowed a public forum to anyone with an articulate cause. Jack London spoke on communism in 1905; Emmeline Pankhurst lobbied for women’s suffrage, and Margaret Sanger for birth control. A young Winston Churchill spoke on the Boer War, and Mark Twain and Booker T. Washington shared the stage at a Lincoln Memorial Meeting. Clarence Darrow debated Ernest Howe on the merits of prohibition and found there were none. When a hall in the nation’s capital was closed to her because of her race, the great Marian Anderson found herself welcome on the Carnegie Hall stage.

In 1892 a fire gutted the Metropolitan Opera House. The Philharmonic Society seized the opportunity and joined the Symphony Society in making its home at Carnegie Hall. The move ignited a rivalry that continued until 1928 when the two organizations finally merged as the Philharmonic-Symphony Society of New York, the official name of the New York Philharmonic.

In 1912, Carnegie Hall presented a concert of early jazz by James Reese Europe’s Clef Club Orchestra. It was the first of many jazz performances including Fats Waller, W. C. Handy, Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Billie Holiday, Dizzy Gillespie, Ella Fitzgerald, Charlie Parker, Oscar Peterson, Sarah Vaughan, Gerry Mulligan, Mel Tormé, Miles Davis, and John Coltrane. A 1938 concert by Benny Goodman and his band marked a turning point in the public acceptance of swing. Duke Ellington made his Carnegie Hall debut in 1943 with the premiere of his tone poem “Black, Brown and Beige,” and when Norman Granz toured his legendary “Jazz at the Philharmonic” programs, featuring the greatest names in jazz, Carnegie Hall was the New York City base.

In 1933, John Jacob Niles was the first folksinger to perform at Carnegie Hall. He was followed by Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Judy Collins, Arlo Guthrie, Bob Dylan, and Joan Baez. Popular entertainers who have performed at Carnegie Hall include Josephine Baker, Judy Garland, Ethel Merman, Nat King Cole, Lena Horne, Frank Sinatra, Liza Minnelli, and Tony Bennett. In 1964, The Beatles made their New York City concert debut, their third live appearance in the US, at Carnegie Hall. They were followed by The Rolling Stones, The Doors, Bob Dylan, Elton John, David Bowie, and Stevie Wonder, and many others.

Carnegie Hall has been the site of numerous television and radio productions including Leonard Bernstein’s Young People’s Concerts, the televised NBC Symphony concerts led by Arturo Toscanini, “Horowitz on Television,” “Carol Burnett and Julie Andrews at Carnegie Hall,” weekly radio broadcasts by the New York Philharmonic from the 1920s through 1962, and “AT&T Presents Carnegie Hall Tonight” in the 1980s. “Live From Carnegie Hall” recordings by artists and entertainers include Paul Robeson, Sviatoslav Richter, Edith Piaf, Glenn Miller, Ike and Tina Turner, Groucho Marx, and others.

The Difficult Years: 1955–1960

Andrew Carnegie sold his industrial holdings to J. P. Morgan in 1900 for $400 million. He devoted the rest of his life to giving away this fortune. Carnegie funded the construction of 2,509 free public libraries at a cost of $56 million. Before he died, he managed to distribute $308 million to public works. When he died in 1919, however, he had not left an adequate endowment for Carnegie Hall. With him died the assurance of continued funding for the halls. In 1925 New York realtor Robert E. Simon bought Carnegie Hall. At the time of the purchase, Simon promised Mrs. Carnegie that he would not demolish the building for a period of five years, or use it for purposes other than those for which it had been originally intended. Simon held to his promise to his death in 1935 despite the steady financial drain of this type of cultural venue and the financial pressures of the depression. His son, Robert E. Simon, Jr. assumed management of the Halls and actually made it profitable for a short period. By the mid-1950s, however, the music business had evolved. It was no longer possible to continue to operate Carnegie Hall in the same fashion. Simon offered the New York Philharmonic an option to buy Carnegie Hall for $4 million. The orchestra was the major tenant, renting the Hall for more than 100 nights a year. Unfortunately, plans were under way for the Philharmonic to move to the new facilities at Lincoln Center. They declined the offer. Though Simon wanted to keep it running, he was forced to offer Carnegie Hall for sale in 1955, under the condition that if a way could be found to save it, the contract would be null and void. A deal was made with a group of developers planning to demolish Carnegie hall and build a 44-story office tower on the site. The deal fell through, but not before the September 9th, 1957 issue of Life magazine showed an artist’s rendering of the proposed fire-engine-red project the developers were contemplating. This helped raise the public awareness of the imminent loss of an institution.

By 1960, with the Philharmonic’s departure set, Simon ran out of options and could no longer afford to keep Carnegie Hall operating. The date of March 31st, 1960 was set for its demolition. At the eleventh hour, the Committee to Save Carnegie Hall, headed by concert violinist Isaac Stern with administrative and financial assistance from Jacob M. Kaplan and State Senator MacNeil Mitchell and others, developed a workable plan. On May 16th, 1960, by special State legislation, New York City was permitted to purchase Carnegie Hall for $5 million. The Carnegie Hall Corporation was chartered as a nonprofit organization and Stern was elected presidentt.

The Future

Carnegie Hall was reborn as a public trust. The nonprofit corporation was to manage and rent the concert hall and could sponsor events as well. Since 1889, Carnegie Hall has had two distinct kinds of boards: The first was Andrew Carnegie’s handpicked advisory board, a largely ceremonial group depending on the generosity of its primary donor. The real philanthropy began in 1960, when The Carnegie Hall Corporation was formed and a board of directors pledged to ensure the Hall’s financial and physical health. To maintain economic viability, the original core mission of showcasing American culture helps ensure that the Hall will remain open to all forms of performance art.

If you would like to use content from this page, see our Terms of Usage policy.

© 2008 Leonard Wyeth & AcousticMusic.Org

Special thanks to The Carnegie Hall website for historical data: www.carnegiehall.org

Information also gathered from Wikipedia – edited and expanded.